The Shima LabSTUDYING LIFE HISTORIES AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN THE SEA |

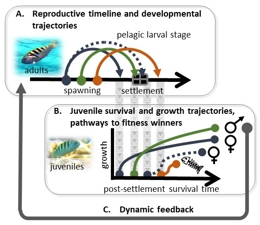

Eco-evolutionary feedbacks......and their contribution to the origin and maintenance of complex life histories“Timing is everything”, or so the saying goes. Birth order and timing of reproduction can determine survival, shape personalities and influence other opportunities for offspring. Are the most successful offspring born at the right time, or just born better? Life-history strategies in the sea. Most marine reef organisms have a complex life-cycle. Adults are often iteroparous and produce many offspring that develop, disperse, and mostly die in offshore waters before settling back to reef habitats. Settlement also is risky. Many species settle at a higher rate during new moons of a lunar cycle when peak tidal amplitudes enhance transport to settlement destinations, and cover of darkness reduces predation rates. Plasticity in developmental time may enable offspring of some species to overcome an inauspicious birthdate (through developmental accelerations or delays) in order to target a good “settlement window”, and potentially alter their fates. Thus, what appears to be a lottery with low odds for survival, may actually be a game that contestants can manipulate to their own benefit. A reef fish’s life is like a “Choose your own adventure” novel. Parents should make decisions about reproductive timing and investment that maximise their own fitness. Environmental uncertainty often selects for iteroparity as a diversified bet-hedging strategy: e.g., reef fish may spawn on a fairly continuous basis, producing offspring with a wide range of birthdates. Larvae spawned at certain times may have better odds of survival (e.g., well-timed to hit a favourable settlement window) than others who were spawned at less advantageous times. However, larvae of many reef organisms also have plastic developmental rates, excellent sensory and locomotory capabilities, and are therefore well-equipped to change where and when they settle. Should an individual settle “on schedule” or would it do better to alter its developmental trajectory to target a particular time or place? The solution is unclear because developmental accelerations or delays can be costly, and strong density dependent interactions may favour individuals that settle out-of-phase with the pack. Such decisions about where and when to settle can strongly affect the future growth and survival of individuals on the reef. Moreover, many reef fish species have socially-controlled sex determination (i.e., sex-change capability). Some of these species exhibit plasticity in maturation strategies (e.g., protogynous hermaphrodites typically mature first as females, with the most dominant fish becoming a male that monopolises matings with subordinates to achieve a large increase in fitness; however, some individuals mature directly as small males and “sneak” matings as an alternate strategy). Birthdates and subsequent developmental decision-making may determine order of arrival, relative growth rates, and positions within dominance hierarchies that can profoundly affect future reproductive fitness. Opportunities for eco-evolutionary feedbacks. Settling reef fish may “choose different adventures” depending upon their developmental histories (past experience) and assessments of future opportunities (habitat quality, local density of conspecifics). The range of possibilities may cause substantial variability in individual growth, survival, and reproductive performance. This is effectively “demographic heterogeneity” (e.g., Noonburg et al 2015), and it has consequences for population dynamics that may, in turn, shape evolutionary processes. Eco-evolutionary dynamics (or “adaptive dynamics”) facilitate exploration of these feedbacks, and allow us to link (using theoretical methods) heterogeneity in demographic fates of individuals (e.g., driven by birthdates and developmental decision-making) to the reproductive decisions of parents (Shima et al, 2018, 2020, 2021). Our ongoing work continues to explore these eco-evolutionary feedbacks, primarily using the sixbar wrasse as a model species.

Key Collaborators

For more information, see:Research publications

Data sets

Sixbar sub-adults (center image) on patch reef within the lagoon of Mo'orea, French Polynesia. |

Observing male courtship in the sixbar wrasse on Mo'orea French Polynesia. |

|

A conceptual model illustrating the interplay between spawning decisions of parents and offspring, their consequences in later life, and a potential 'eco-evolutionary' feedback that may lead to the evolution of extreme iteroparity. |

||

Juvenile sixbar wrasse (center-right) associated with pocillopora coral. |

||

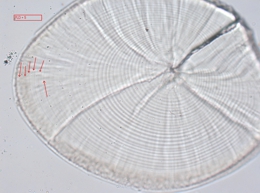

An otolith of a recently settled sixbar wrasse, used to reconstruct birthdates and developmental histories.

|

||

Return to Research index

|

||